Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe aroma of bread and butter lingers, and plates are filled with freshly cooked samosas and cups of hot, creamy Iranian milk tea.

These are some of the spots you usually see in an Indo-Persian cafe.

Popularly known as “Iranian cafes”, these iconic restaurants, with their iconic marble-topped tables, vintage clocks, checkered floors and unique menus, have been a part of Indian culture for over 100 years.

Their influence has spread beyond India: Dishoom, one of London’s best-known restaurant chains, was inspired by these cafes.

When Persian immigrants from Iran arrived in large numbers in the 18th and 19th centuries, they appeared in cities such as Bombay and Pune.

There is a third, lesser-known region of the country – the southern city of Hyderabad – where these cafes have been an intrinsic part of the local culture for decades.

Despite having lots of charm and a rich cultural heritage, the city’s cafes – like those in Pune and Mumbai – are on the verge of extinction, with owners blaming rising prices, competition from fast-food restaurants and Changes in consumer tastes.

To this day, Hyderabad is second only to Mumbai in terms of the number of Iranian cafes. This is because the city was the center of trade in Iran in the late 19th century.

Under the rule of the Muslim Nizam, or prince, Persian was widely spoken. Niloufer Café is located in the old part of the city and is actually named after the Nizam’s daughter-in-law, an Ottoman princess.

This was also a time when parts of modern-day Pakistan were still in India and Iran was its neighbor, making it easy for Persian traders to enter the country.

Most families who moved to Hyderabad and other Indian cities did so to escape persecution and famine back home. Some people come here in search of better jobs and businesses.

Their arrival coincided with the colonial period, when the British were actively promoting tea-drinking culture in the country.

When the Iranians arrived, they brought their own style of making tea, forming a unique Iranian tea culture in the city.

In Iran, people drink it without milk, but with a sugar cube in their mouth. However, Indians add milk and cream to their tea to flavor it.

“Initially, the tea was sold as Chai Khana and only Muslims drank it,” said Hyderabad historian Mohammed Safiullah. “But soon, people from all religions fell in love with it Unique taste.”

By the 20th century, Iranian cafes were popping up in every corner of Hyderabad.

Customers chat in the coffee shop for hours while sipping mouth-watering tea.

In some cafes, customers can play their favorite songs on the jukebox for a small fee.

Historians say these cafes played a crucial role in breaking down social barriers and religious taboos and became an important part of the city’s public life.

“Hyderabad’s Irani cafes have always been a symbol of secularism,” says historian Paravastu Lokeshwar. “These names do not have any religious connotation. People of all religions and castes patronize them.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNow they are under threat.

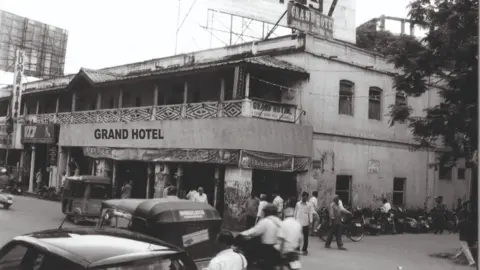

Jaleel Farooq Rooz, owner of the famous Iranian cafe The Grand Hotel, said that more than two decades ago, there were an estimated 450 cafes in Hyderabad, but now only 125 remain.

Mr. Lutz’s maternal grandfather came from Iran in 1951 and took over the hotel, which was founded in 1935 by 12 Iranians.

“We used to sell 8,000-9,000 cups a day. Now we’re only selling 4,000 cups a day,” he told the BBC.

He believes competition from fast-food chains is one reason. Hyderabad, now one of India’s fastest growing cities, remained a quiet town until the early 1990s. Things changed in the mid-1990s, when the city joined India’s IT boom and became a hub for the industry.

This transformation comes with a series of economic reforms in the country, which has allowed global fast food chains and cafes to penetrate the Indian market. Similar to Iranian cafes, these food outlets also offer more seating options, but with better facilities and more choices.

Ruiz said most Iranian cafes operate in rented premises because they need ample space where customers can relax and drink tea.

But rising property prices in Hyderabad have forced many owners to take up other jobs.

“Inflation has also taken its toll. Prices of tea powder and milk powder have tripled from five years ago,” he added.

Others say the number of Iranian families entering the industry has also declined.

“The current generation is not interested in the cafe and restaurant business. They prefer other jobs and many migrate to other countries,” said Mahmood (who only goes by one name), owner of the popular Farasha restaurant.

But despite the challenges, some in the industry continue to swim against the tide.

Syed Mohammed Razak manages the Red Rose restaurant in Hyderabad. His grandfather immigrated from Tehran and built the City Lights Hotel in the 1970s. Later, Mr. Razak’s father founded the Red Rose restaurant.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr. Razak, an engineer and graphic designer by profession, admits that “just selling milk tea and biscuits” is neither easy nor profitable.

He is now introducing new dishes to the menu to attract more customers and is using his graphic design skills to expand the business and promote it online.

“I want to carry on the family legacy,” he said.

Not just the owners, but also loyal customers – many of whom have frequented these cafes for generations – who say they always come back for “just another cup of Iranian milk tea.”

“Iranian tea is a part of my life. I like its taste and drink it every time I go out,” Yanni said.

“There’s nothing like it even today.”

This article was corrected on July 12, 2024, to clarify that traditional Iranian tea is not made with milk or cream.