Picture a Saturday morning in Santa Monica in the year 2080.

That’s the potential future if climate change continues unabated, according to a new mapping tool from researchers at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. The tool draws a direct line between a region’s expected climate 60 years from now and the region currently experiencing that climate.

Matt Fitzpatrick, a professor of global change ecology and the tool’s creator, said the map is “a really interesting way to communicate to people the magnitude of climate change we can expect.”

He noted that sometimes warnings about global warming—such as international 1.5 degrees Celsius limitor predictions that the Earth will warm by 5 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century—may feel distant or difficult to comprehend.

“These analyzes are a way for people to really understand this,” Fitzpatrick said. “It’s a way to turn these abstract numbers into something more concrete and meaningful.”

Positive and impactful reporting on climate change, environment, health and science.

The results are remarkable.

Under a high-emissions scenario, or if fossil fuel consumption and global warming continue unchecked, Los Angeles would warm by about 7.7 degrees in the summer and 5.6 degrees in the winter, with the overall climate more similar to the current conditions in Rialto , a city in southwestern San Bernardino County.

San Francisco will feel more like Jamul, a census-designated place in San Diego County not far from the Mexican border where summer temperatures are 8.5 degrees warmer and winter temperatures are 6.4 degrees warmer.

Sacramento feels like the Garnet area near Palm Springs in Riverside County, with summer temperatures 10.4 degrees warmer and winter temperatures 7.1 degrees warmer.

It’s not just the temperature that changes. The map lays out how precipitation is changing, with summers and winters expected to become wetter and warmer in many parts of California. However, Fitzpatrick points out, Droughts may remain more common Because warm conditions cause soil to dry out faster.

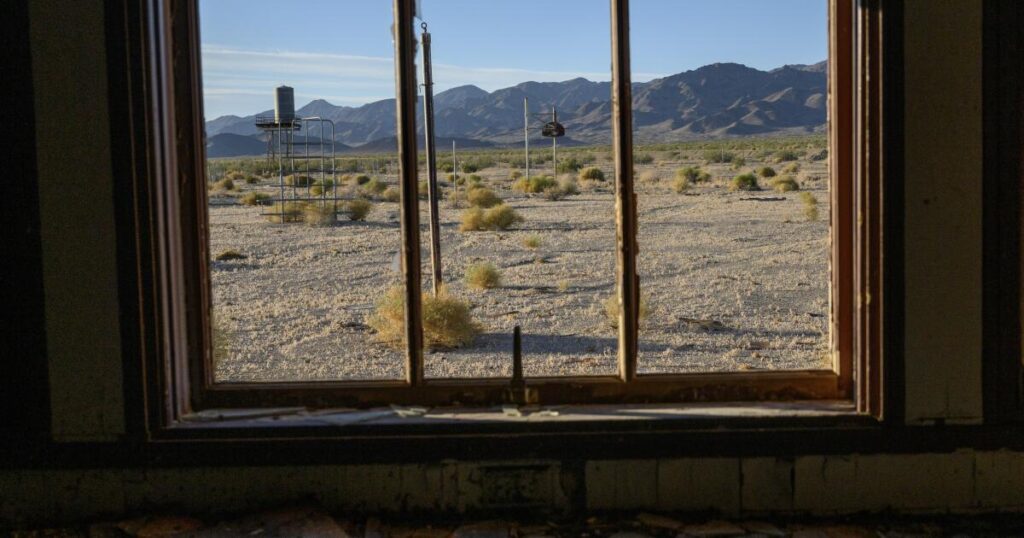

Maps show vegetation is also expected to shift amid global warming, with places such as Redding shifting from Mediterranean landscapes defined by woodlands and scrub to desert or dryland scrub similar to Arizona’s Fountain Hills.

Fitzpatrick said the tool uses models from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and various other research groups to make comparisons.

“I’m taking the data generated by these models and doing a relatively simple statistical analysis, and I say, here are the projections for the greater Los Angeles area at the end of the century, and then I say, where on Earth do we have this climate today?” he said.

But it also lays out the risks faced by those who are dissatisfied with outcomes in their areas by comparing different outcomes based on humanity’s ability to reduce emissions that drive climate change.

In a lower emissions scenario that limits fossil fuels, Santa Monica’s best climate simulation would be Castaic, not Rialto.

Fitzpatrick modeled different outcomes using two specific scenarios outlined by the intergovernmental panel.

The high-emissions scenario used for modeling sees CO2 emissions doubling from current levels by 2100, leading to a steady increase in temperatures, with average global warming exceeding 6 degrees by the end of the century.

In that world, food supplies will be affected and competition for resources will become more intense. Economic development will slow down, as will investments in education and technological development, among other things.

The low scenario is considered the most optimistic. It depicts a world in which global carbon emissions are slashed to net zero around 2050 and society transitions to a more sustainable path that limits global warming to 2.7 degrees Celsius or 1.5 degrees Celsius. Inequality will be reduced and health and education will improve. While some extreme weather events will still occur, many of the worst consequences of climate change will be avoided.

The difference between the two scenarios is evident in the map tool. Fitzpatrick said that in the high-emissions scenario, the average distance to the closest climate match was about 620 miles, while in the low-emissions scenario it was less than half that distance, and in some cases less than a hundred miles. .

“The longer we wait, the harder it will be to solve this problem, but it’s not hopeless. There’s still a lot we can do to avoid the worst effects,” he said. However, “We are now conducting a huge experiment on Earth, and things could go very wrong. Scientists could also easily underestimate the results.” [as] They may overpredict.

In fact, Bill Patzert, a retired climatologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Canada-Flintridge, said the tool’s findings are likely conservative.

He said August and September temperatures in Los Angeles are already about 7 to 8 degrees warmer than they were at the beginning of the 20th century, so while it’s not surprising that the map reaches a similar conclusion for 2080, the reality is likely to be worse.

“The curve will continue to increase,” Pazett said. “The weather will continue to get warmer, and more than that – I guarantee it will be warmer than [this map] Say, 10, 20, 30 years from now, the impact will be more severe than it was in the past 20 years.

What’s more, Pazett said the map could do more to educate people about the impacts of these changes, including worsening wildfires, reduced water supplies and adverse impacts on human health and the economy. Extreme heat is already the deadliest climate hazard, and heat-related mortality will be high by 2080, he said.

“This is no longer an academic exercise,” Pazett said. “This is a serious matter and the impact will be more serious from now on than it was in the 20th century.”

While maps draw direct connections, there is usually not just one analogy for any given location. In fact, the map’s “climate similarity surface” feature suggests that Los Angeles in 2080 will look like parts of Algeria, Jordan and Western Australia today.

Additionally, some cities don’t have anything similar – meaning there’s no direct comparison to how warm those places will be in the future. These include some areas near the equator and some areas in the Middle East, such as Aden, Yemen.

The map says of Aden: “Future climate at this site is expected to be different from that currently found anywhere on Earth, so there is no climate match for this site.”

Significant changes have also occurred in other parts of the world. In the high-emissions scenario, New York City feels like part of Texas; Chicago feels like part of Oklahoma; and the map shows that Miami feels like part of Saudi Arabia. Internationally, Dublin feels like Spain’s Basque Country; London, like France’s Nouvelle Aquitaine; and Rome, like Berat, Albania.

Fitzpatrick said he chose to focus his analysis on 2080 because it is far enough away to show the magnitude of the expected impacts, but close enough to be within the lifetimes of many people and certainly within the lifetimes of those who will “live through this whole thing.” change.

One unintended consequence, Fitzpatrick said, is that some people like what they see, such as parts of Germany projected to feel more like Italy by 2080.

“I wasn’t really expecting this,” he said. “But the opposite of that is, it might be good for you, but overall, it’s really bad for other people. You all know this in California.

communication

Towards a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter on climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation and solutions.

From time to time you may receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.