When the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling last month on anti-camping laws, Pasadena Mayor Victor Gordo was among the local political leaders who welcomed it.

The high court concluded that laws punishing homeless people for sleeping or pitching tents in public places did not amount to cruel and unusual punishment. That means cities can clear homeless encampments in parks, sidewalks and other areas even if they lack enough shelter beds.

Gordo said his city intends to increase enforcement, but in a compassionate way — providing shelters and other services while regulating parks and sidewalks.

“Individuals will get the help they need,” he said. “But we cannot allow people to simply occupy public spaces and parks while refusing assistance.”

Staff from Mayor Karen Bass’ Inside Safe program spoke with homeless residents at an encampment at 86th and Broadway last month.

(Brian Vanderbrugg/Los Angeles Times)

Gordo said the ruling gives his city new flexibility to respond to the crisis and “removes excuses that prevent us from doing so.” The responsibility to act is now up to all of us. In Pasadena, that’s what we set out to do.

In Los Angeles’ Eagle Rock neighborhood, which borders Pasadena, City Councilman Kevin de Leon seemed less than enthusiastic about the court’s decision. De Leon said he worries the ruling will incentivize smaller cities around the East Side to force homeless people out.

“If you’re a homeless person and you feel constantly harassed, you self-evict and move to downtown Los Angeles,” he said.

Political leaders in Southern California responded to the Supreme Court’s ruling with a range of reactions, with some expressing relief and others appearing anxious.

Some expressed gratitude to the justices for clarifying the legal standards for enforcement, which they said were muddied by lower court rulings. Others openly worry that neighboring cities will take punitive measures, sending police to encampments to hand out tickets but failing to build enough shelter and permanent housing.

The issue is particularly sensitive in Los Angeles, where enforcement of the city’s anti-camping laws varies from neighborhood to neighborhood. The law, called 41.18, targets key locations such as schools and day care centers and is not a city-wide ban.

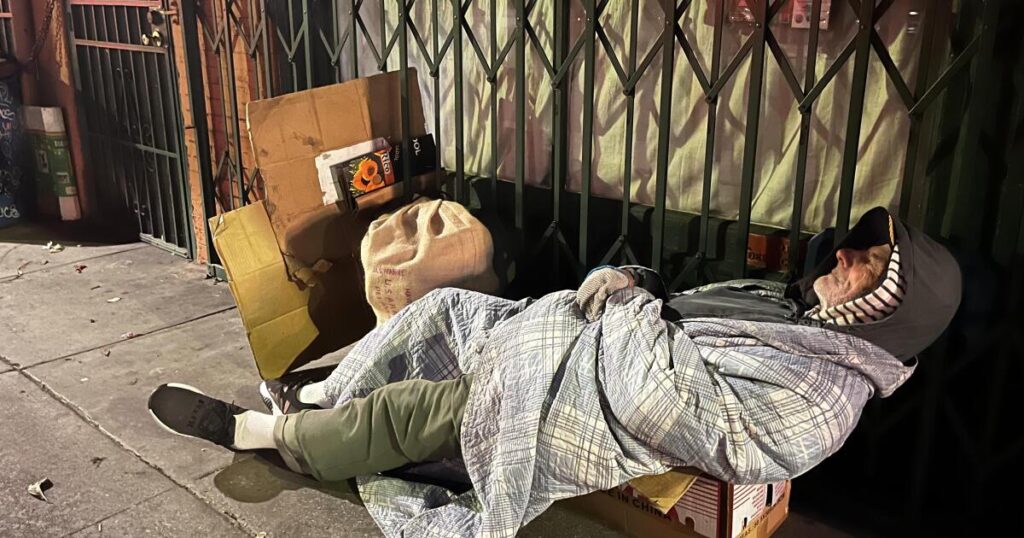

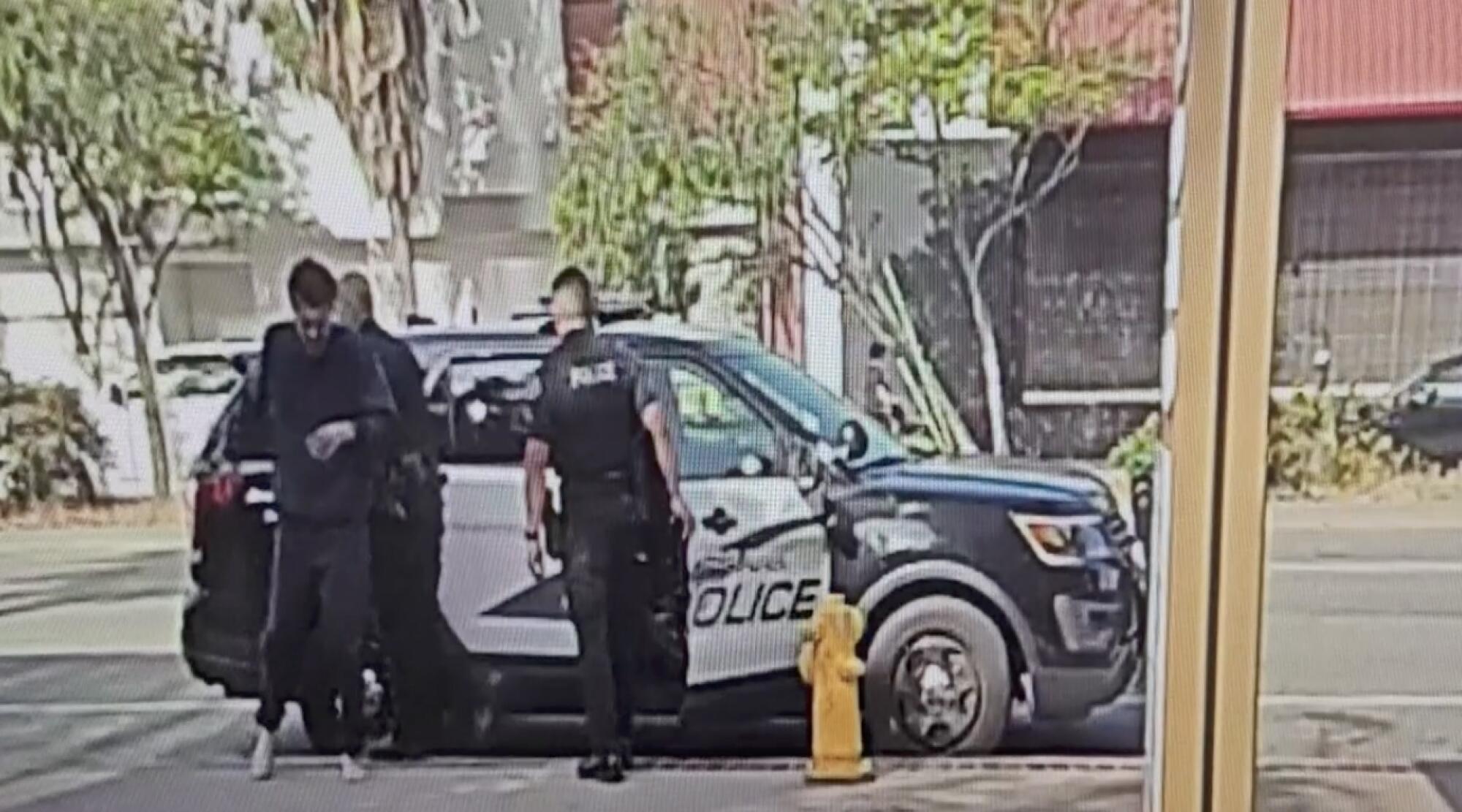

Several city leaders pointed to a recently released video showing Burbank police leaving a shoeless homeless man outside the North Hollywood office of Los Angeles Council President Paul Krekorian on the sidewalk. The video captured the man lying on the pavement, sparking calls for a criminal investigation into him.

Surveillance footage provided by the office of Los Angeles City Council President Paul Krekorian shows Burbank police driving a homeless man to North Hollywood.

“I’m very, very concerned that what you’re seeing in Burbank may be happening more and more,” Mayor Karen Bass said the day the ruling was issued. “If cities could ticket people and kick people out, I would be very concerned about an increase in the number of people moving to Los Angeles from other cities.”

Elsewhere in the region, some are voicing the same concerns, but in reverse — that Los Angeles will push a large homeless population into their neighborhoods.

“Most of the people I spoke to locally were concerned that the LAPD would chase homeless people into their city,” said the Redondo Beach city attorney. Mike Webb’s city has an outdoor homeless court that uses misdemeanor prosecutions as a pathway to shelter and housing.

Weber said that in the six years since the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the Eighth Amendment’s Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause prohibits criminal penalties for “sitting, sleeping, or lying outside in a public place,” he hopes cities Ability to abandon harsh enforcement policies.

Weber said that since the Supreme Court ruling, he has begun discussions with officials from other South Bay cities to establish a “neighbor commitment.”

“It would be nice to have a good neighbor commit that they’re not trying to displace homeless people in their area, but instead make homeless people aware of the resources that are available to them,” Weber said.

“I think it’s a wonderful idea,” said Shayla Myers, an attorney with the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles who has filed numerous lawsuits over the city’s treatment of its homeless population. “The reality is that criminalizing homelessness doesn’t solve homelessness. It just pushes people from one place to another.

Myers said she hopes the city attorney will view the decision narrowly, taking into account protections from the U.S. Constitution, other parts of the California Constitution and “necessary” defenses against prosecution for violating anti-camping laws.

“The Supreme Court sometimes tells us what jurisdictions can do, but they don’t tell us what jurisdictions should do,” she said. “For a place like Los Angeles, which has 89 jurisdictions, it would be disastrous if the cities within the county were locked in a race to the bottom.

Tanaka Richardson collects her belongings at 86th Street and Broadway in South Los Angeles, the site of the latest Inside Safe encampment operation.

(Brian Vanderbrugge/Los Angeles Times)

Anti-camping laws have been a contentious area of law since at least 2018, when the Ninth Circuit blocked Boise, Idaho, from clearing encampments because the city lacked enough shelter beds.

The Supreme Court declined to review that decision, but this year it took up a similar case against the city of Grants Pass, Oregon. There are not enough beds in the shelter to sleep in some public areas.

The High Court overturned the Court of Appeal’s decision in a 6-3 decision. The ruling clears the way for cities to resume enforcement of laws idled by the Ninth Circuit or strengthen laws that were watered down to comply with the ruling.

In Southern California, several city officials contacted by The Times said it was too early to say how the ruling would affect their policies.

Torrance Mayor George Chen said the city will review its ordinance following the Grants Pass decision. Monrovia City Manager Dylan Fike said his city is awaiting a letter of legal advice. Santa Monica officials said they will continue to implement “robust, broad and innovative strategies to address homelessness.”

In August 2023, Armando Darnas entered his tent at the Urban Alchemy Safe Sleep Village in Culver City.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

San Bernardino spokesman Jeff Krause said the ruling provides “much-needed clarity.”

“It confirms that cities like San Bernardino have the legal authority to maintain and clean public property and make public property available to all residents, not just those experiencing homelessness.”

The Grants Pass case has created deep philosophical divisions among California politicians, even among Democrats. Gov. Gavin Newsom, San Francisco Mayor London Breed and the Los Angeles city attorney. Hydee Feldstein Soto calls on the Supreme Court to address anti-camping laws and the Ninth Circuit’s ruling in Grants Pass.

Long Beach Mayor Rex Richardson said on Instagram that last month’s decision provides new tools for cities “hampered by legal ambiguity that limits our ability to implement common-sense measures to protect the well-being of our residents.”

Los Angeles County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath responded harshly, calling the ruling “unreasonable.”

Bass, who attended an event with Horvath to mark the region’s progress on homelessness, said the decision would “spark a new wave of criminalization.”

“This is a repeat of the 1990s, when we didn’t know how to deal with social problems like drug addiction and gang violence. We just decided to lock everyone up. That’s what I’m more concerned about [more] More than the buses that take homeless people to Los Angeles,” she said.

Bass’s comments came on a day when officials reported a 5.1% decline in the number of homeless people — people living in tents, makeshift camps, cars and other vehicles — in Los Angeles County. 10.4%. The mayor used the numbers to argue that punitive approaches are ineffective.

“Giving people tickets and punishing them — how are they supposed to pay for the ticket? What happens when they don’t pay? Does it go into a warrant and now it gives us an excuse to jail someone? Those are failed responses. We knew it wasn’t going to work,” she said.

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass, pictured in San Francisco last month, said she worries the Grants Pass ruling will spur some cities to push homeless residents out of Los Angeles

(Josh Adelson/The Times)

Los Angeles’s anti-encampment laws have a narrow focus. Camping is prohibited within 500 feet of schools and day care centers. City councils can also designate “sensitive” areas — libraries, highway overpasses, homeless shelters and other locations — as off-limits areas.

Bass has focused much of his efforts on the “Secure Inside” program, which has moved more than 2,800 homeless residents into hotels, motels and other forms of temporary housing. So far, 539 of them have been placed in permanent housing, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

Los Angeles City Councilwoman Traci Park, who works with Bass on Operation Inside Safe in Venice, Mar Vista and Del Rey, praised the mayor for providing more temporary housing for the homeless. But she had a different view of Grants Pass, saying the court made the “legally correct decision.”

Tatayana Noles packs her bags during an encampment operation run by Mayor Karen Bass’ Inside Safe program at 86th and Broadway.

(Brian Vanderbrugge/Los Angeles Times)

Even before the Supreme Court ruling, Parker said, her coastal area had already seen an influx of homeless people, some of whom had moved from other parts of the country. Enforce laws regarding outdoor activities and the number of newcomers will increase.

“If the city of Los Angeles does not correct course, we will ultimately have to deal with a regional, statewide and national crisis,” she said.

Seven city council members, including Parker, called on the city’s legal team to review outdoor camping laws enacted by the other 87 cities in Los Angeles County. A vote on the review is expected sometime after the council’s summer recess.

Parker’s district borders parts of Culver City, which voted last year to ban camping on sidewalks and other public areas. Still, Culver City Councilman Dan O’Brien expressed similar concerns, saying his city lacks the resources to serve every homeless person arriving from Los Angeles

O’Brien said Culver City — a community surrounded by Los Angeles — has been working to move homeless residents into hotel rooms, converted motels, a new “Safe Sleep” health village and other locations.

“We know where our homeless people are coming from and provide care and housing and need Los Angeles to do the same for them,” he said. “Sometimes the second part is a challenge.”

Times staff writer Jasmine Mendez contributed to this report.